|

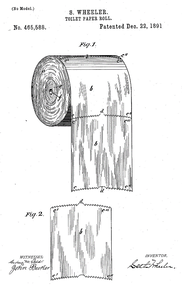

There is a story spiritual teachers sometimes tell to teach about spiritual transformation. It’s about an ice cave Rishi (a Himalayan baba) whose spiritual practice is a form of yoga in which he meditates on the inner light. After many years of this practice, the Rishi eventually attains the highest state of samadhi. Despite his high spiritual state, the Rishi still needs meager supplies to support his life in the Himalayas. So, the time eventually comes when he has to descend to the village at the foot of the mountains to secure supplies: another blanket, a stick, and a bowl. Walking through the bustling village streets, the Rishi is overwhelmed and anxious. He isn’t used to having to share his personal space with anyone. Then, one fellow gets too close and bumps up against the Rishi, knocking him into another person. The Rishi turns and snaps: “Watch where you’re going, you idiot!” This story is used to teach the lesson that the measure of one’s spiritual life is not inner experience but the quality of one’s interactions with other people. As Jesus said, “You shall know them by their fruits”: (love, patience, kindness, etc.) In this time of pandemic, many of us, not Himalayan baba’s but “villagers,” are being tested in a similar way. We are being called from our worldly, intensely social lives to sequester – our own version of the overly crowded marketplace, or living room, as the case may be. This experience is taking its toll on many people. We’re just not that used to being forced into such close proximity with others for so long! Along these lines, have you noticed how many articles and videos are being posted these days about whether relationships will survive this period of social isolation? Here’s a couple of examples: “Marriage Wasn’t Built to Survive Quarantine,” and, “Love Under Lockdown: How Couples Can Cope During Covid-19.” If the literature is at all indicative, couples are struggling with each other… parents are struggling with kids… and kids are struggling with kids. Why the struggle? Dynamics that were once alleviated by our social outlets are now inescapable. We can’t put off or ignore disagreements. Private time is a rare commodity. Dishes are piling up in the sink! My partner doesn’t even know which way the toilet paper is supposed to roll off the toilet paper roll (What was I thinking when I married this scoundrel?!)! (By the way, there is a correct way to roll the toilet paper off the toilet paper roll!) In sum, we are “suffering” unmediated, 24/7, interpersonal intensity! (As Sartre said, “Hell is other people.”) This unmediated, 24/7, interpersonal intensity is testing our nerves… and measuring our spiritual lives. How go our interactions with the people with whom we are sequestered? Do we find ourselves acting with love, patience, and kindness, or, like the Himalayan baba, quipping: “Watch where you’re going, you idiot!” Where are we landing on the “reactivity continuum”? For those of you who are struggling with this unmediated, 24/7, interpersonal intensity, I want to suggest a way to reframe this period of social isolation. The Sufi tradition is particularly helpful here because the Sufi tradition understands that the measure of one’s spiritual life is the quality of one’s interactions with other people. Even more, the Sufis see our interpersonal relationships with other people as preparation for Divine love. As Jami says: "You may try a hundred things but love alone will release you from yourself. So never flee from love - not even love in an earthly guise - for it is a preparation for the supreme Truth." Similarly, Rumi says: There is no salvation for the soul But to fall in Love. It has to creep and crawl Among the Lovers first. What Rumi and Jami are telling us is that part of the journey to God takes place through our interactions with other people. That is, it’s not until we learn to love people - unconditionally (meaning, no matter what way they think the toilet paper should roll off the toilet paper roll!) - that we are ready for Divine love. Another way of saying this is that the path to God is an alchemical path; a transformative path that requires all the complexity of human relationship to work its magic. In the end, though, we learn to love and thereby become able to receive Divine love. As we struggle with our interpersonal relationships during this sequester, it would be helpful to see our struggles as indicators of the work we need to be doing on ourselves, from a spiritual perspective. Rather than seeing the other scoundrel(s) in our lives a problem set(s), we need to see him/her/them as opportunities - opportunities to enact love, patience, kindness, etc., even, or especially if, we find these scoundrels unworthy! In his book, “The Only Dance There Is,” Ram Dass cuts to this chase. When I first read this over thirty years ago it struck me to my spiritual core. Since then, I have returned to it over and over and over again. I suggest printing it and pasting it to the bathroom mirror. It’s a simple but effective mnemonic device: The only thing you have to offer another human being, ever, is your own state of being. You can cop out only just so long, saying, I’ve got all this fine coat – Joseph’s coat of many colors – I know all this and I can do all this. But everything you do, whether you’re cooking food or doing therapy or being a student or being a lover, you are only doing your own being, you’re only manifesting how evolved a consciousness you are. That’s what you’re doing with another human being. That’s the only dance there is!

There is purported to be a Chinese curse (No Chinese source has yet been found, however.) that masks as a blessing: “May you live in interesting times.” Well, we certainly do live in interesting times! We are facing the first worldwide pandemic in one hundred years. The global economy has been seriously shaken thrice in the last two decades. Most everyone reading these words clearly remembers the events of 9/11 and the wars that followed. Advances in science and technology are increasing exponentially, as are their detriments. The world faces ecological havoc, the likes of which threaten our very existence. And, for all its blessings and curses, the “internet of things” is knocking on our doorstep (I will be doing a sermon about the onset of A.I. this spring.). The list can be made very long... these are definitely interesting times!

This all reminds me of a teaching story from the Sufi tradition:

“Jesus (upon whom be peace!) saw the world revealed in the form of an ugly old hag. He asked her how many husbands she had possessed. She replied that they were countless. He asked whether they had died or been divorced. She said that she had slain them all. ‘I marvel,’ said Jesus, ‘at the fools who see what you have done to others yet still desire you!’” Now, this could easily turn into an anti-worldly message. That seems to be its trajectory, does it not? But we’re going to peel the worldly onion one layer deeper than that. Rather than push back against the world, with all its vicissitudes, we are going to set this teaching story in the larger context of Jesus’ other teachings. We begin by asking, did Jesus deprecate life in the world? He did not. Quite the contrary! Jesus saw the world as the abode of the kingdom, per the Gospel of Thomas, “The kingdom of God is spread out upon the earth,” and the Gospel of Luke, “For in fact, the kingdom of God is among you.” The problem, said Jesus, was not life on earth. The problem was that “people do not see it [the kingdom of God].” This gets to the crux of Jesus’ ministry. His ministry did not aim, as modern day evangelistic preachers tell us, at delivering people from this miserable world into a perfect, eternal state of heaven. Jesus’ ministry aimed at helping people see that they already inhabit the kingdom; that the kingdom is spread out among them now. Jesus’ was the quintessential spiritual optometrist! Well, if Jesus taught that the “kingdom of God was spread out upon the earth,” why would he, per the Sufi teaching story, marvel at the fools who see what the world has done to others yet still desire the world? It’s all about desire and identification, those forces that cloud one’s vision like a cataract of the soul. The earth is the realm of the sacred. And, it is inhabited by us creatures of desire. The spiritual life is the art of knowing the proper limits of desire (we must survive, after all), coupled with the ability to keep one’s eyes (and mind and heart) open to the sacredness in which we are enmeshed. When desire dominates, as it does with those (most) that live for the gratification of desire, the capacity to recognize life’s sacred depth is proportionately compromised (One cannot take in the lilies of the field when one is constantly digging for diamonds.). The result is an over identification with the objects of gratification: money, power, fame, food, sex... whose transitory and fleeting nature ultimately bring suffering (classic Buddhist teaching). Those who live life for the gratification of desire, who are over identified with the objects of gratification, are ultimately “slain” by the world. That is, their spirits are depleted by the suffering that follows from the pursuit of what is transitory and fleeting; never realizing the sacred depth of life that offers ongoing sustenance and innate joyfulness. Knowing this, Jesus’ counseled a shift of attention = a turn of the mind (metanoia) = “repentance.” He aimed to reawaken us to the kingdom by calling our attention to different objects, objects that are doorways to the sacred: the lilies of the field, the birds of the air, the vineyards and the fields rips for harvest... the nature theme in general. (For those wanting to explore the imagery of nature themes in Jesus’ teaching, the work of Niel Douglass-Klotz regarding Jesus’ words in the original Aramaic is very informative.) Indeed, every phenomenon of nature, from the flowering fields to the running rivers to the floating clouds will, if we are receptive enough to the experience, open a doorway to the sacred. Once we successfully turn our attention to the sacred and enter therein, our greatest longing is satisfied – our longing to know we belong to the greater reality of which we are, in essence, a part. When this occurs, when that longing is satisfied, desire returns to its proper place in our lives and we are no longer identified with the world’s objects of gratification. It is then that we are able, as Jesus’ counseled, to live in the world but not be of it. Being in the world but not of it is the reconciliation of Jesus' teaching that “The kingdom of God is spread out upon the earth” with the simultaneous recognition that the world slays all who marry her. We need not deprecate life in this world, only engage it from our identification with Spirit. Now, pause and breathe deeply... hear the birds calling to you out your window... respond to that call with your mind and heart... and enter in... Namaste, Alex "God cannot be thought but God can well be loved." – "The Cloud of Unknowing"

There is a similar phenomenon for many people on the spiritual path. Like the gambler, many spiritual sojourners feel as though they are perpetually living on the precipice of living the spiritual life. They, too, have some sense of being on the verge... near completion, fulfillment - of some sort. So they keep searching... for that one last bit of esoteric knowledge that will finally deliver the goods. Then life will be as they imagine - as it should be! They, too, say over and over again, "Let it ride, baby! Let it ride!"

The people to whom I refer are those - and there are many - who tend to "think the path." That is, they are those who believe, consciously or not, that they can think their way along the spiritual journey. The truth is, however, that the spiritual journey is not a thing that can be thought, as the opening citation to this post, from The Cloud of Unknowing, advises us. That is, spiritual experience is not a mental experience, nor, for that matter, is it an emotional experience (though paradoxically, the heart is the path, on which more in a future post). Rather, it is an experience that is had when the mind, emotions, and the body are at rest; when, through spiritual practice, the input from these three centers has faded into the background of one’s awareness. In such a state, which entails such notions as devotion, surrender, and grace (more on the role these notions play in spiritual practice, also in a future post), one is prepared to receive spiritual experience. None of this is to say that the mind does not have a place in the spiritual life. It certainly does. For instance, the mind is needed to acquire information about the path. At the same time, spiritual experience is dependent upon the ability to relinquish the mind, to resist the temptation to confuse information about the path with the path itself. In sum, to receive spiritual experience is to have direct experience of spiritual reality. Such direct experience is not only not dependent upon the mind, it has the prerequisite of "no mind." Returning to our opening metaphor, direct experience requires that one stop rolling the dice! Then, and only then, will the game be over. Then and only then will one know that one knows that one knows what it is that one seeks to know - which truly cannot be "known!" Sit (don't think) with that for a while. Give up that bad gambling habit, friends, and sit, instead. You've already hit "black 17"! You just don't know it yet. Namaste, Alex A bird took flight. A flower in a field whistled at me as I passed. I drank from a stream of clear water. And at night, the sky untied her hair and I fell asleep clutching a tress of God’s. When I returned from Rome, all said, “Tell us the great news,” and with great excitement I did: “A flower in a field whistled and at night, the sky untied her hair and I fell asleep clutching a sacred tress…” Musing on this piece by St. Francis is a good follow up to my last post, in which I mused on Mirabai’s poem, “A Hundred Objects Close By.” That’s because this poem invokes the “book of nature,” the centuries old notion (esp. the Middle Ages, to wit, Megenberg’s 14th century "Buch der Natur") that nature, as much as books of revelation, reveals to us the sacred depth and meaning of God’s creation. “The heavens bespeak of the glory of God while their expanse declares the work of His hands.” – Psalm 19 On the one hand, the book of nature complements books of revelation (or vice versa). Indeed, as mentioned in my last post, sages from the world’s various religious traditions, some of whom are central figures in these very books of revelation, themselves invoke nature in their teachings: the lilies of the field, the lotus flower, mountains, wind... rainfall. It only makes sense that revelation, which is said to reveal God’s will, be consistent with God’s own creation: a harmony between nature and revelation just intuitively makes sense.

This raises an interesting question though, intimated by this poem. If it makes sense that the book of nature and books of revelation be harmonious, which has more authority, especially in those instances wherein the two seem to contradict one another? One obvious example, given the theme of this post, is the theological doctrine that creation is “fallen,” which points to the further, logically implicit theological doctrine that human beings are inherently sinful; “born into sin.” Given that there is so much beauty and goodness in the creation, do these theological notions not run against the intuitive grain? Do not the book of nature and books of revelation (in this particular case, the New Testament) seem to contradict one another? Those who would be prone to defend these theological doctrines can easily point to the “problem of evil.” They may ask: “Doesn’t the fact of evil in the world, from tsunamis to humankind’s aggressive tendencies, demonstrate the truth of these doctrines?” It certainly must be admitted that natural disasters and humankind’s destructive tendencies are undeniable realities in this world. However, it may be countered, what about the “problem of the good?” The evidence of beauty and tenderness in the creation far outweighs the “problem of evil.” For every tsunami that occurs there are countless fiery sunsets, golden meadows, surging mountains, and flowing rivers. For every act of human aggression committed there are myriad examples of acts of compassion, often unnoticed but present nonetheless - present and deeply indicative of our essential human nature: spontaneous acts of compassion between children and moments of deep tenderness demonstrated to those in need. Yes, there is misery in the world and people can behave “sinfully.” At the same time, beauty permeates the creation and human beings are capable of profound goodness as well. If we admit beauty and goodness as an equal part of the creation, if not even a predominant part of the creation, then the theological narrative of the “fall” is out of step with the book of nature. Pray tell, what then? Should theological doctrine determine our thinking (and behavior) or the book of nature? I think St. Francis is informative here... Would St. Francis have sacrificed his fellowship with nature and the “great news” he learned from it in favor of theological doctrine? Or, would he have turned his mind away from such theological meanderings and gone back to sleep in a truss of God’s hair, leaving it to Rome to pontificate on such matters? Regarding this question of authority, St. Francis seems to be indicating that nature trumps revelation, or at least the Church Fathers’ interpretation of revelation, if not revelation itself (though I suspect he would hold to that as well). After all, when St. Francis returned from Rome, the seat of Church authority, with everybody chomping at the bit to hear the “great news” from Rome, he opted to read them the book of nature. There is a profound anti-authoritarian impulse in St Francis, which could be interpreted as heretical. At the same time, one could also interpret St. Francis’ answer as a simple reminder not to lose faith with the creation itself and that the creation itself, if we bother to read the book nature, is already informing us about life’s sacred depth and meaning. “We do not,” he could be understood to be saying, “need theological mediators.” Tennyson was correct when he said “nature is red in tooth and claw.” At the same time, he was remiss not to point out that nature is far more often cooperative and caring than it is aggressive (Darwin did attempt to convey this message in “The Origin of Species” but the message was missed.). Now, I’m off to smell the roses and take in those other “hundred objects close by.” Namaste, Alex In my previous post, A Misty Morning Musing, I raised the topic of the difference between occupying a dualistic perspective on the world verses occupying a nondual perspective, known in Eastern mystical traditions (originally in the philosophy of Vedanta) as advaita (dvaita = “two or three (or more)”; a-dvaita = “not two or three (or more)”). In sum, advaita, or the nondual perspective, is the perspective in which one experiences oneself as an aspect within the unity of being, being, as it were, “unified in a seamless whole, as in that Eden like state wherein Adam and Eve walked in union with God...” Now, this can quickly become an overwhelming philosophical concept for the uninitiated, as I also indicated in my previous post. At the same time, it is a very important concept to understand from at least two perspectives: the mystical and the ethical. So, stay with me as I lead you to the ethical import of this philosophy. I think you will find advaita key to understanding not only mysticism in general but the ethical implications of mysticism as well (to wit, Jesus – yes, Jesus was, in my reading of him, an advaitist, as his ethics clearly indicate). Indeed, there are significant ethical implications that arise from mystical states, a subject not given nearly enough due - most people merely seeking the “mystical high” without regard for the demands that follow from such experience. One of the best and simplest descriptions of advaita that I have encountered is in J. D. Salinger’s short story, “Teddy.” Teddy is a ten year old boy who is the reincarnation of an advanced soul. As such, Teddy fascinates as a type of “mystic-savant” (to steal an apt phrase from Kenneth Slawenski). He possesses exceptional intelligence and an apparent ability to know what ought not to be knowable (for instance, there are several places in the story where Teddy correctly anticipates the day and manner of his death). Regarding Teddy and advaita, there is a point in the story where Teddy relates his first mystical experience: "I was six when I saw that everything was God and my hair stood up," said Teddy. "It was on a Sunday. My sister was only a tiny child then. She was drinking her milk and all of a sudden, I saw that she was God and the milk was God. I mean, all she was doing was pouring God into God, if you know what I mean." In sum, it’s all God. Now, advaita can be understood on two levels. First, it can be understood as an abstract idea. This is to understand advaita as a philosophical principle. Second, it can be understood as subjective reality. This is to understand advaita as a mystical perception. This latter understanding of advaita is what interests us, especially in regard to its ethical implications. For this we invoke Jesus... In The Gospel of Matthew we find a story of Jesus meting out judgement: To some, he says: “Come, you who are blessed. Take your place in the kingdom, for I was hungry - and you fed me... I was a stranger - and you welcomed me... I was sick – and you cared for me... I was in prison - and you visited me.” These blessed ones questioned Jesus, saying, “Lord, when did we see you hungry, or as a stranger, or sick, or in prison, and helped you?” Jesus replied, “Truly I tell you, whatever you did for the least of these, you did unto me.” To others, he says, “Depart from me, you who are cursed, for I was hungry - and you did not feed me. I was a stranger, and you did not welcome me... I was sick – and you did not care for me... I was in prison - and you did not visit me.” These cursed ones questioned Jesus, saying, “Lord, when did we see you hungry, or as a stranger, or sick, or in prison, and did not help you?” Jesus replied, “Truly I tell you, whatever you did not do for the least of these, you did not do unto me.” Now, if we approach this scripture from the dualistic perspective, it will read as an ethical charge to care for “the least of these,” meaning all people in need. This is no mean ethical charge. Indeed, it is quite profound! At the same time, from the dualistic perspective other people – including “the least of these” - remain as objects; ultimately separate from us. Hence the protest, “Lord, when did we see you hungry, or as a stranger, or sick, or in prison...” Read from the advaitist perspective, however, this scripture has an even more profound meaning and makes even more sense in the context of Jesus life and ministry. No one, including “the least of these,” is separate from anyone. People are not objects to which one applies ethical principles. Rather, all of us are aspects within the unity of being, being, as it were, “unified in a seamless whole, as in that Eden like state wherein Adam and Eve walked in union with God...” Hence, Jesus was the hungry, the stranger, the sick, the prisoner... not in an abstract, philosophical, thought experiment sense but in actuality. Indeed, we, too, are the hungry, the stranger, the sick, the prisoner... there simply is no separation of being(s). It is this advaitist perspective that the mystical Jesus held and it is from this perspective that his ethics originate. It is only when we understand this that we truly understand Jesus’ words: “...whatever you did for the least of these, you did unto me.” Sit and absorb that for a moment! In sum, when we consider Jesus’ life and ministry from the perspective of advaita, we discover a much richer, more compelling, and truer sense of who Jesus was (a Jewish mystic) and how he exhorted us to live our lives. From a mystical perspective we are to realize that we already exist in a sacred reality: “The kingdom of heaven is spread out about you.” From an ethical perspective, we are to act in the world as though our every action ripples through the entirety of creation, from the smallest single celled organism to the Divine itself: “you did unto me.” "I am he As you are he As you are me And we are all together... goo goo g'joob..." - The Beatles tat vam asi (“thou are THAT”) my friends,

Alex

Splash! Godot wasn’t taking in the scene but becoming part of it, already cresting the once still water. Elbow deep, he turned to me with that particular stare he has that communicates, “Well, I’m waiting? Isn’t this why we are here?!” Before doing my duty I had to take an extra moment to absorb it all. Godot traipsed impatiently while I watched this thought cross my mind: “It would be so awesome, actually to be in that scene myself, maybe standing in the midst of that angelic mist on the far shore, like Adam surely did innumerable mornings in Eden...” [No. I am not a creationist. It’s literary license… ;-)] Then, with a few whirls to gain momentum, I let the bumper fly. I love that moment of silence as the bumper arcs through the air, the magic of physics keeping it aloft just long enough to create a brief, meditative vision, until - another splash! Off swims Godot and while he retrieves said bumper, my mind returns to that Eden like scene. And, just as quickly, I realize the absurdity of that vision. I already am standing in the midst of that angelic mist on the far shore, like Adam surely did innumerable mornings in Eden! I had simply failed to see it because of my perspective. And what perspective was that, pray tell? It was the dualistic perspective we all inhabit when we are ego identified. It is natural to be identified with our egos but when we are, we are also trapped in a false, dualistic perspective. That is, when ego identified I experience myself as subject and everything that is “not me” as object. Hence, I, the subject, did not experience myself as being part of this morning’s exquisite scene - the object. Such dualistic perspective is the cause of our perceived alienation from life, which in turn is the cause of a great deal of our suffering - on which more in some future post. However, once I realized the absurdity of my Eden like vision I was able to become free of the false, dualistic vision of the world I was experiencing. With a simple shift of attention I became unified in a seamless whole, as in that Eden like state wherein Adam and Eve walked in union with God - until someone told them they were naked (yet another post for another time, or, if you wish, you can catch me sermonizing on that topic here on YouTube.) What I am speaking about here is what is called "advaita" in the Eastern mystical traditions; the unity of Being beneath appearances. This is a vitally important theme, both for the mystical experience and for the ethics that it entails. If this is all starting to wax too philosophical, consider Hafez’s simpler, more humorous take on the same theme: “I laugh when I hear that the fish in the water is thirsty.” Namaste,

Alex This post is the fourth (and final) in an informal series (maybe you’ve noticed the interplay between these four posts) on love and realization. The first post, Where There Is No Love There Is No Enlightenment, connected love with realization/enlightenment. The second post, Those Who Don't Feel This Love, expanded on the subject of love. The third post, A Legacy of Lies?, asked the question whether one believes there is an essential (Divine) self even to realize. In this post I ask the question, what price is one willing to pay to attain realization of one’s essential (Divine) self? As stated in my last post, motivations for the spiritual journey vary and most motivations are insufficient to the task. I then suggested that the belief that one has an essential (Divine) self that one can discover is from whence proper and sufficient motive arises. This point is beautifully and simply expressed in Jesus’ parable of the pearl of great price. “The kingdom of heaven,” said Jesus, is like unto a merchant seeking goodly pearls. When he found the pearl of great price he went and sold all that he had and bought it. This is not a difficult parable to understand but in order to understand it in the context in which we are considering it, i.e., spiritual motivation, we need to tease it out a bit. First, we need to understand that the kingdom is not an afterlife abode promised to believers. Rather, it is something that already lies “within you” (Luke, Ch. 17). In other words, the kingdom is the realization of one’s essential (Divine) self. (I know there are those who would debate this understanding but this post is not for that debate.) Second, let us consider the merchant. It is important to note in this parable that Jesus chose a merchant to make his point, rather than some generic figure (He could have simply said, “...a man...”) So, why a merchant? The merchant is someone who peddles in the acquisition and sale of fine things. This means two things. One, he possessed a chest of riches. Two, being a peddler of fine things he would recognize the value of the pearl (Many people might have “eyes to see” but still not see. It has always been the case that many people seeking spiritual wisdom fail “to see it” when they see it.). Third, and most pertinent for us here, the merchant sold all that he had (his chest of riches) to obtain the pearl. That is, he was motivated enough to obtain the pearl that he was willing to pay the highest price he could. Now let’s consider that price. By selling all he had to obtain the pearl the merchant was sacrificing his livelihood, the means by which he provided for his personal security: food, clothing, shelter, etc. This is no mean feat, especially in Jesus’ day when one’s livelihood was an all-consuming (24/7) endeavor. But the merchant understood: the price one is willing to pay for a thing is in direct proportion to one’s motivation to obtain that thing. Such is the value of the kingdom/realization. The pursuit of realization is a costly endeavor - one’s life as one currently knows it. One must undergo a reevaluation of one’s life context and the influences therein, then make the decision to relinquish the egoic attachments that do not support the spiritual journey. This usually requires significant life change, including everything from the material one chooses to read to how one spends one’s free time to with whom one chooses to spend one’s time. All such choices indicate the price one is willing to pay – or not. There is another saying attributed to Jesus: “Many are called. Few are chosen.” I am not a Biblical literalist so sometimes find myself reinterpreting what I read therein, in a manner more consistent with the other mystical traditions I study (I consider Jesus a mystical Jew – not a Christian). In this case I have reinterpreted Jesus’ words thusly: “Many are called. Few Choose.” (Matthew, Ch. 22) I prefer this version of Jesus’ words because, well, given my own study and practice they seem likely to be more historically accurate. And, this puts the onus of responsibility on the individual rather than God. Truly, isn’t this where it belongs, anyway? Now, what say ye? Ego, or, agape? Namaste,

Alex In 1876 the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche penned these words: If the doctrine of sovereign becoming; the lack of any cardinal distinction between man and animal – doctrines which I consider true but deadly – are thrust upon the people for another generation with the rage for instruction that has by now become normal, no one should be surprised if the people perishes of petty egoism, ossification, and greed, [then finally] falls apart and ceases to be a people. In its place systems of individualist egoism, brotherhoods for the rapacious exploitation of the non-brothers, and similar creations of utilitarian vulgarity may perhaps appear in the arena of the future. In numerous citations scattered throughout Nietzsche’s corpus the philosopher proved uncannily prophetic. This citation is no exception. In it he speaks about the effects Darwinism would have upon humanity, as the teaching of evolution became more widely known. He warned that rampant egoism would prevail if we came to understand ourselves as arising from the swamp rather than having a transcendent origin. It is hard to debate the fact that we now live in an age in which rampant egoism is ascending. Was Nietzsche right? Is this rampant egoism attributable to the loss of belief in a transcendent origin? Let us look at this question from the perspective of the mystics. As mentioned in my previous post (see “What Is Faith?”) the mystics believe that we have both a lower nature and a higher nature; that we are both physical and spiritual beings (i.e., we have a transcendent origin). The lower (physical) nature operates through the ego. The higher (spiritual) nature manifests Divine virtues. Hence, the aim of the spiritual journey is the transformation of being, from the dominance of lower (physical) nature to higher (spiritual) nature. Complete transformation of being is the state in which the ego, eventually free from the influence of lower (physical) nature becomes the vehicle for the manifestation of Divine virtues, e.g., compassion, forgiveness, charity… unconditional love. From the point of view of the mystics then, if we abandon belief in our higher (spiritual) nature there is no transformation of being to be had. There is no motivation, let alone possibility of becoming anything other than what we already find ourselves to be. We shall forever be dominated by our lower (physical) nature, trapped in the egoic state, which has no other agenda than personal survival. The ego thus left to rule, Divine virtues lay dormant while egoic tendencies dominate: self-centeredness, instinctual gratification, the use of the other (people, animals, and natural resources) as means to personal ends, etc. Does this mean that Nietzsche was right, that rampant egoism is attributable to the loss of belief in a transcendent origin? Not entirely, not even from the mystics’ point of view. Mystics have always understood the transformation of being to be a great struggle; the vast majority of people have always served their lower (physical) nature in lieu of their higher (spiritual) nature (“One cannot serve both God and mammon,” taught Jesus). Our modern age is somewhat exceptional, however, in that the tendencies of the lower nature are exacerbated in a world in which capitalism and materialism are held up as evidence of one’s personal, even existential worth (that mammon thing again…). In sum, the loss of belief in our transcendent origins may contribute to the rampant egoism we see in today’s world but capitalism and materialism (and other factors) also contribute to this phenomenon. It’s a complex situation... While it is not a panacea, we do need to return to belief in a transcendent origin in order to help counteract rampant egoism. This belief is not rooted in wishful thinking nor is it a psychological strategy conjured up simply to counteract rampant egoism. Rather, it is a known truth rooted in the mystics’ direct experience of our essential nature. We are, the mystics tell us, sparks of the Divine and being such, our essential nature partakes of Divine virtues: compassion, forgiveness, charity… unconditional love. By returning to belief in a transcendent origin we can resume the project of the transformation of being, a project jettisoned with the rise of Darwinism. This is what we modern mystics have to offer our world, namely, the possibility of becoming other than what already find ourselves to be. It is our task, even our destiny to become vehicles for the manifestation of Divine virtues, as the Shvetashvatara Upanishad tells us: “Hear, O children of immortal bliss!

You are born to be united with the Lord.” Spiritual fads come and go (Yes, you guess rightly. This is a critical take on “The Secret.” Hopefully that does not mean I will lose its fans before the end of this post.). “The Secret” is one such fad whose time should have come and gone by now, at least according to my calculation. But over and over again I see it reappear in all its New Age glory. "The Secret" is a supposed spiritual principle that holds that focused concentration on certain desired goals (e.g., objects, situations, wealth) will help one realize said goals. To buttress the claim, advocates of "The Secret" invoke its many famous historical adherents, such as Plato, Newton, and Emerson. Setting aside this logical fallacy of the argument from authority, which in and of itself ought to raise suspicion about "The Secret," let us focus on the principle itself. "The Secret" begs the question, Why would someone on a spiritual journey desire certain goals (a Tesla, a bigger house), situations (a particular job, a particular relationship), or wealth (nuff said). The answer proponents of "The Secret" give is why not?! Well, here's the rub, folks... "The Secret" is a form of New Age prosperity preaching with which the soul holds no kin. The aim of the spiritual journey is a journey from ego identification to self-realization (Who am I, really?) Any spiritual journey that does not bring one to this realization is an ego masquerade Given that, the problem with "The Secret" is easily identified, namely it promises egoic treasures which not only serve the ego alone, they are impediments on the path to self-realization Despite the argument, the ego may pose the acquisition of objects can aid the journey or are fruits to be harvested along the way, "The Secret" does not lead to self-realization. It is a New Age dead end. Rather than spend one's time in meditation with focused concentration on desired objects, one ought to spend one's valuable practice time relinquishing such desires in order to come closer to one's true self, which is already perfected. That is, one's true self neither needs nor desires the objects of egoic satisfaction that "The Secret" promises. Once this is realized, one realizes that a better use of a spiritual practice is the cultivation of the Divine qualities inherent in one's true self: compassion, forgiveness...unconditional love, etc. A spiritual life that bears these fruits will quickly realize the secret of the "The Secret." If this critique does not convince you of the secret of "The Secret," consider swami Puppetji's take on the matter... It’s 2:30am here in Kerela, my fifth night on pilgrimage in India and still I am not adjusted to the time change. There’s a 10 and a half hour difference between here and home. So, I am enjoying being wide awake in the middle of these glorious Kerela nights. And what a productive time this has proved to be! I’ve completed four blog posts so far in these wee hours of the morning. Though best not to try this at home for the gift will surely wane as I become accustomed to Kerela time. But before that happens I will leverage my sleeplessness, hoping to create an audio blog. Our theme during these ten days in Kerela with Russill Paul is healing. We are discussing the importance of healing the egoic structure while we walk the spiritual path. This is an important topic because it is our woundedness around which the ego constricts and that constriction is part of what prevents the surrender necessary in one’s practice. Anyone who honestly reflects on their life surely can identify the numerous wounds with which they are afflicted. There are wounds we suffered in childhood at the hands of others who expressed their own woundedness on our childhood innocence. There are wounds we suffered in childhood as we ourselves thoughtlessly hurt others, only to feel the remorse of our transgressions after the fact. And of course there are wounds we have suffered in adulthood, again, because of what others have done to us or what we have done to others. (You’ll notice here that even when it is we who are the culprit we still suffer wounds ourselves. Self-recrimination sets in and we carry that with us throughout our lives. No transgressor gets off conscience free!) In all this conversation about woundedness a question is begged, namely, “Who, ultimately, is to blame for my woundedness?” While we can clearly point to culprits, even ourselves at times, the fact of the matter is that no one is to blame for our woundedness. “But wait!” you might be protesting. That scoundrel clearly wounded me! Well, on one level that is true. On another level that scoundrel can point to yet another scoundrel who caused their woundedness and had it not been for that experience, they would not have wounded you. When their transgression toward you occurred they were coming from a place of woundedness themselves. Given this, are they then to blame? No more than you are when you wound others when you act from woundedness. In otherwords, transgressions that cause woundedness are born out of transgressions that caused woundedness which are also born out of transgressions that caused woundedness. It’s an infinite regress of woundedness and unless you buy into the Christian explanation that it all began with Adam, the only person who cannot point to his own woundeness as a justification for his actions, no one is to blame. This reminds me of a story I once heard in a Philosophy class as an Undergraduate at The University of Michigan. A school teacher was lecturing on the nature of the universe and had just finished explaining the mechanisms of our own solar system. When she asked whether the class had any questions a young girl raised her hand and asked a question most everyone wonders upon seeing a visual representation of the solar system for the first time: “How does the earth manages to stay in its place?!” Another hand immediately shot up and without waiting to be called upon a young boy shouted, “I know! “I know! It sits on the back of a giant turtle!” The amused teacher saw a perfect teaching moment and gently inquired of the boy. “And on what does the giant turtle sit?” The boy paused for a moment then responded, “It sits on the back of another giant turtle!” The bemused teacher couldn’t help but inquirfurtherthinking that with this next question her point would surely be made. “And on what does that turtle sit?” she asked. “Why, another giant turtle!” exclaimed the boy. “And THAT turtle?” inquired the increasingly impatient teacher. “Why,” said the boy, “it’s turtles all the way down!” In case you missed the relevance of this humorous anecdote relative to our topic, it is this. Don’t look for culprits. Wounds are not healed in a court of moral law as no one is to blame. Accusations and justifications will go on forever in the search for a conviction, which is ultimately a fruitless endeavor - though the ego will find temporary satisfaction in the attempt.

Rather, notice the ego’s tendency to contract around your woundedness and have the courage to relax that contraction – without first requiring that culprits be identified. As difficult as this is it is very important for your spiritual practice and hence for your spiritual journey, because the contracted state of the ego is not in fact protecting you from your woundedness. Quite the contrary - it is preventing your progress, both psychologically and spiritually.

In order to understand this we must take a moment and consider the mystics' understanding of human nature. The mystics believe that we have both a lower nature and a higher nature; that we are both physical and spiritual beings. The lower (physical) nature operates through the ego. The higher (spiritual) nature manifest Divine virtues. This understanding of human nature is what accounts for the moral struggles we humans face in life. We feel an inherent tension between our lower (physical) nature and our higher (spiritual) nature, that is, we would like to manifest Divine virtues but our ego often overpowers our best intention. Thus the moral struggle, which the apostle Paul illustrates so well in his letter to the Romans: ...what I am doing I do not understand, for I am not practicing what I would like to do but I am doing the very thing I hate... I find then that evil is present in me, the one who wants to do good, for a while I joyfully concur with the law of God in the inner man, I see a different law in the members of my body, waging war against the law of my mind and making me a prisoner of the law of sin... The mystics further teach that the spiritual journey is a journey of the transformation of being, from the dominance of lower (physical) nature to higher (spiritual) nature. Complete transformation of being is the state in which the ego, eventually free from the influence of the lower (physical) nature becomes the vehicle for the manifestation of Divine virtues. Then one acts with compassion, forgiveness, charity...unconditional love. This is what the prophet meant when he said that faith manifests itself through the ego, that faith is "the knowledge of the heart, the words of the tongue, and the actions of the body." It is also what Jesus meant when he said, "you will know them by their fruits." As for his part, Paul was still ripening at the time he wrote his letter to the Romans, as are we all, in this season of life...

There is a straw man run amuck in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Greg Epstein, Humanist Chaplain at Harvard University, has proffered that one can be “good without God.” The book has received wide acclaim, more for the title, I suspect, than the reasoning contained therein. In fact, so popular is the book’s title that it has spawned a billboard war between believers and nonbelievers. But that is not why I throw my fellow Harvardite under the theological bus. Well then, pray tell?

The problem with Epstein’s book is not the title’s proposition, that nonbelievers can be morally good despite a lack of belief in a deity. Anyone not blinded by the right and who has the least bit of sociological savvy can observe that faith is not a prerequisite to living the moral life. Hence, Epstein’s argumentation toward this end amounts to a rather moot point (though his is an admittedly kinder, gentler Humanism than the likes of Dawkins and Hitchens). Rather, the problem with the book is that the title’s proposition itself rests upon a shaky proposition, namely, that the notion that one cannot be good without God has ever had traction beyond the minority Christian movement we call “the Christian right,” which happens to be wrong about most things theological (which in turn begs the question as to why intelligent Humanists with the public’s ear continually deplete their air time engaging that community). If Humanists want to engage the religious world in a constructive way (of course continual publications attacking theological straw men does fascinate the public and so predictably sell books, which may be their ultimate goal, in lieu of genuine dialogue) a better point of contact begins with the following proposition: The aim of the religious life is the transformation of being toward the end of realizing one’s full human potential. And, it might be added, that that potential is hardly tapped by merely living the moral life. It was Voltaire who said that “God made mankind in His image and mankind returned the favor.” But whether mankind is a construction of God’s or God is a construction of mankind’s, the notion of the imago dei (to be made in the image of God) speaks to my very point. In the imago dei we have the highest conception of human potential in that the imago dei represents an amalgamation of the highest virtues: compassion, forgiveness… unconditional love. In the end, this is that toward which the religious life calls us via the transformation of being. In sum, merely to live the moral life, while laudable, is no remarkable achievement and certainly is not something that requires belief in God. Indeed, those who thusly view the religious life utterly fail to understand the religious life. The point of the religious life is the transformation of being; it is to hold out the invitation to become other than we already find ourselves to be - to be better than merely good. Can we be good without God? Of course we can. But, we can be better with… |

Archives

March 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed