|

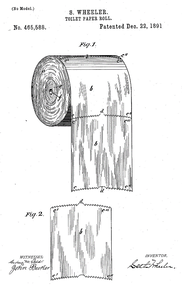

There is a story spiritual teachers sometimes tell to teach about spiritual transformation. It’s about an ice cave Rishi (a Himalayan baba) whose spiritual practice is a form of yoga in which he meditates on the inner light. After many years of this practice, the Rishi eventually attains the highest state of samadhi. Despite his high spiritual state, the Rishi still needs meager supplies to support his life in the Himalayas. So, the time eventually comes when he has to descend to the village at the foot of the mountains to secure supplies: another blanket, a stick, and a bowl. Walking through the bustling village streets, the Rishi is overwhelmed and anxious. He isn’t used to having to share his personal space with anyone. Then, one fellow gets too close and bumps up against the Rishi, knocking him into another person. The Rishi turns and snaps: “Watch where you’re going, you idiot!” This story is used to teach the lesson that the measure of one’s spiritual life is not inner experience but the quality of one’s interactions with other people. As Jesus said, “You shall know them by their fruits”: (love, patience, kindness, etc.) In this time of pandemic, many of us, not Himalayan baba’s but “villagers,” are being tested in a similar way. We are being called from our worldly, intensely social lives to sequester – our own version of the overly crowded marketplace, or living room, as the case may be. This experience is taking its toll on many people. We’re just not that used to being forced into such close proximity with others for so long! Along these lines, have you noticed how many articles and videos are being posted these days about whether relationships will survive this period of social isolation? Here’s a couple of examples: “Marriage Wasn’t Built to Survive Quarantine,” and, “Love Under Lockdown: How Couples Can Cope During Covid-19.” If the literature is at all indicative, couples are struggling with each other… parents are struggling with kids… and kids are struggling with kids. Why the struggle? Dynamics that were once alleviated by our social outlets are now inescapable. We can’t put off or ignore disagreements. Private time is a rare commodity. Dishes are piling up in the sink! My partner doesn’t even know which way the toilet paper is supposed to roll off the toilet paper roll (What was I thinking when I married this scoundrel?!)! (By the way, there is a correct way to roll the toilet paper off the toilet paper roll!) In sum, we are “suffering” unmediated, 24/7, interpersonal intensity! (As Sartre said, “Hell is other people.”) This unmediated, 24/7, interpersonal intensity is testing our nerves… and measuring our spiritual lives. How go our interactions with the people with whom we are sequestered? Do we find ourselves acting with love, patience, and kindness, or, like the Himalayan baba, quipping: “Watch where you’re going, you idiot!” Where are we landing on the “reactivity continuum”? For those of you who are struggling with this unmediated, 24/7, interpersonal intensity, I want to suggest a way to reframe this period of social isolation. The Sufi tradition is particularly helpful here because the Sufi tradition understands that the measure of one’s spiritual life is the quality of one’s interactions with other people. Even more, the Sufis see our interpersonal relationships with other people as preparation for Divine love. As Jami says: "You may try a hundred things but love alone will release you from yourself. So never flee from love - not even love in an earthly guise - for it is a preparation for the supreme Truth." Similarly, Rumi says: There is no salvation for the soul But to fall in Love. It has to creep and crawl Among the Lovers first. What Rumi and Jami are telling us is that part of the journey to God takes place through our interactions with other people. That is, it’s not until we learn to love people - unconditionally (meaning, no matter what way they think the toilet paper should roll off the toilet paper roll!) - that we are ready for Divine love. Another way of saying this is that the path to God is an alchemical path; a transformative path that requires all the complexity of human relationship to work its magic. In the end, though, we learn to love and thereby become able to receive Divine love. As we struggle with our interpersonal relationships during this sequester, it would be helpful to see our struggles as indicators of the work we need to be doing on ourselves, from a spiritual perspective. Rather than seeing the other scoundrel(s) in our lives a problem set(s), we need to see him/her/them as opportunities - opportunities to enact love, patience, kindness, etc., even, or especially if, we find these scoundrels unworthy! In his book, “The Only Dance There Is,” Ram Dass cuts to this chase. When I first read this over thirty years ago it struck me to my spiritual core. Since then, I have returned to it over and over and over again. I suggest printing it and pasting it to the bathroom mirror. It’s a simple but effective mnemonic device: The only thing you have to offer another human being, ever, is your own state of being. You can cop out only just so long, saying, I’ve got all this fine coat – Joseph’s coat of many colors – I know all this and I can do all this. But everything you do, whether you’re cooking food or doing therapy or being a student or being a lover, you are only doing your own being, you’re only manifesting how evolved a consciousness you are. That’s what you’re doing with another human being. That’s the only dance there is!

In my last post ("Where There Is No Love There Is No Enlightenment") I wrote about the importance of discerning between realized and unrealized teachers. In sum, it is less important what a teacher professes than the quality of that teacher’s Presence; the extent to which the fruits of the Spirit shine through him/her. Of course, the greatest fruit of the Spirit is agape, unconditional love. I went on to end that post by reminding us that we, too, are called to embody agape. After all, each of us is on the path to our own realization, are we not? (For more on this, see my next post…) Given this, this seems like a good time to emphasize the point, with a little help from Rumi. In his poem, “Those Who Don’t Feel This Love,” Rumi says, “Those who don’t feel this Love pulling them like a river… let them sleep.” He goes on to say that the study of theology is “trickery” and “hypocrisy.” The significance of this juxtaposition of heart and mind is indispensable to the spiritual journey and has even greater meaning when one understands that it is also deeply biographical for Rumi. Those who don't feel this Love pulling them like a river, those who don't drink dawn like a cup of spring water or take in sunset like supper, those who don't want to change... let them sleep. This Love is beyond the study of theology, that old trickery and hypocrisy. If you want to improve your mind that way... sleep on. I've given up on my brain. I've torn the cloth to shreds and thrown it away. If you're not completely naked, wrap your beautiful robe of words around you… and sleep. Rumi’s father was a great scholar and Rumi followed suit. He was trained in Islamic law and served as an Islamic Jurist. In other words, he was an expert in the social and personal application of Islamic theology. In short, his was a religious life of the mind alone. Enter Shams…

Shams-e Tabriz was a dervish (a Sufi ascetic) and Rumi’s encounter with him radically changed Rumi’s life. Rumi and Shams developed a profound spiritual friendship and a deep love for one another. Indeed, after shams was killed (some believed he was killed because of a suspected homosexual relationship between the two) Rumi wrote the Divan-e Shams-e Tabrizi, a lengthy lyrical poem in which he expressed his love (and bereavement) of Shams. Thereafter, Rumi spent the remainder of his life as a love mystic and mystic poet, having come to understand that the path to Spirit was through the heart, not the mind: “I’ve given up on my brain. I’ve torn the cloth to shreds and thrown it away.” Shams had lit the spark of Divine Love within Rumi and Rumi’s life was forever changed. He saw the limitations of a religious life centered in the mind and thereafter became a lover of God. He wrote of this love in a myriad of ways in his plethora of poems. Elsewhere he says: “There is no salvation for the soul but to fall in Love,” and, “The Rose of Glory can only be raised in the Heart.” There is a strong affinity between Jesus and Rumi that lies in their eschewing of rational theology in favor of Love in matters of the Spirit. “One cannot serve both Mammon and Spirit,” said Jesus. Likewise, said Rumi, “Those who don’t feel this Love pulling them like a river… let them sleep.” Jesus and Rumi are thus exemplars of the Spirit and to fail to understand their emphasis on Love is to fail to understand the Presence they bequeathed to the world. They realized within themselves the possibility that remains dormant within each of us - agape as modus operandi. This of course begs a question, namely, how do we awaken to that Love that we might also embody the same quality of Presence as the likes of Jesus and Rumi (They are not exceptions to the rule but prototypes of human possibility.)? Awakening to Love implies a willingness to enter into a loving relationship with Spirit that is commonly omitted from people’s spiritual lives these days (I mean as a subjective experience rather than as an abstract idea.). Yet consider this. If “God is love,” as stated in First John, does it not follow that God would desire a loving relationship with us? Of course it does, and that relationship is twofold. In the first place, we are to minimize our egoic attachments to the world and set our minds on the Love of God. Hence, a life of meditation and prayer. In the second place, our actions in the world are to be consistent with that Love. Hence, an ethical life that reflects the fruits of the spirit (see previous post). These two things combined, meditation and prayer, and an ethical life, are the foundations of a life of devotion that will awaken one to Love. Ease yourself into the current, dear friend… let Love pull you like a river… Namaste, Alex There is a popular poem by Rumi that begins: The way of love is not a subtle argument. The door there is devastation. There is much that can be said about this part of the poem, especially about the relationship between love and devastation but I will save that for another post at another time. What I want to discuss today is the second half of this poem: Birds make great sky-circles of their freedom. How do they learn it? They fall, and falling, they are given wings. I have a thing for raptors. I have always been mesmerized by their ability to stay aloft on invisible air currents. Sure, I understand the physics of all this. Nevertheless, I find the sight mesmerizing. Visually, it strikes me as an incredible act of freedom. Indeed, I spent many an hour one particular summer taking in such sight while seated on a butte in the Badlands of South Dakota. This is probably why the second half of Rumi’s poem interests me so much. Those “great sky-circles of freedom” reflect my own deep desire. Like Rumi, I, too, wonder, “How do they learn it?” Rumi gives the answer. “They fall, and falling, they are given wings.”

Have you ever wondered what it would be like to be a bird leaving the nest for the first time, hundreds or thousands of feet above the ground, never before having taken flight - falling… falling… falling… before ever having used your wings? What a tremendous act of faith that must be! What a risk taking! What a thrill! What fear! What hope! Yet without leaving the nest that first time, without tumbling into the unknown one cannot fall and if one cannot fall, one cannot be given wings. Of course Rumi is using this as a metaphor, by means of which he wishes to convey a spiritual lesson. In simple terms that lesson is this: one must let go of what one knows before one can become what one will become. Risk, Rumi is telling us, is the prerequisite for spiritual growth. What is it that Rumi wants us to risk? Everything! Spiritual growth requires that we free ourselves from the narrative we hold in our heads about who and what we are. We must relinquish our identification with everything from the historical facts of our being to the subjective experience of our being. That is, we must let go of things like birthdates, achievements, family dynamics, financial successes (or lack thereof), and romantic successes (or failures). We must let go of things like addictions, aversions, anxieties, pleasures, and neuroses. These historical facts and subjective experiences comprise the narrative that we hold in our heads about who and what we are. This narrative is our psychological nest. Rumi is telling us to let it go - to tumble into the unknown. Leaving this nest would seem an easy thing to do but it is not. The truth is that we are adamantly attached to that narrative. It is our identity, for better or worse. Relinquishing it is a daunting prospect. But until we do, until we leave this nest through an act of faith, until we take that risk, until we experience the thrill, the fear, and the hope such leave taking entails, we will not fall and if we cannot fall, we cannot be given wings. Come! Soar with me! Namaste Alex |

Archives

March 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed